The novel coronavirus COVID-19 has precipitated an unprecedented health and economic crisis. But the need to transition to carbon- neutral energy systems over the next few decades remains. In fact, the economic crisis has made carbon pricing and supporting measures even more urgent. Energy prices need to reflect both the supply and the environmental costs of fuel use to ensure private investments when recovery is well underway are adequately allocated to low-carbon technologies. And carbon pricing generates a new revenue stream that can contribute to fiscal needs which have become even more dire as a result of the crisis.

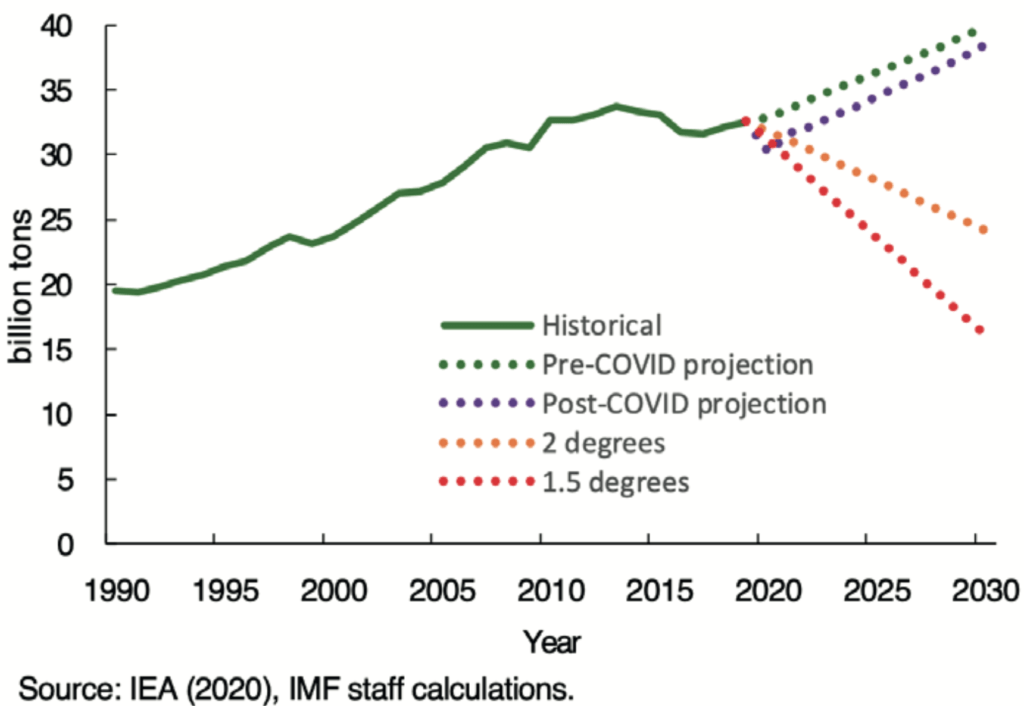

Global Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions

To prevent dangerous instability in the global climate system, fossil fuel CO2 (and other greenhouse gas) emissions need to fall rapidly— by about 25 percent below 2018 levels by 2030 to contain future warming to 2oC, or 50 percent below for the 1.5oC target (and continue to decline thereafter). Emissions this year are projected to be about 8 percent lower than in 2019, due to both lower GDP and structural shifts in the economy, like more remote working. However, emissions are projected to start rising again next year as economies recover and some of the structural shifts are reversed. Our latest projections suggest that in the absence of new mitigation actions 2030 emissions will be about 20 percent above 2018 levels (albeit moderately smaller than in pre-COVID projections).

The Paris Agreement provides the international framework for meaningful action on climate mitigation. At the heart of the Agreement are the commitments, made by 190 parties, to reduce their emissions. These pledges will be revised ahead of the United Nations climate meeting, re-scheduled for November 2021 in Glasgow. Although the immediate challenge is for countries to implement these pledges, at the global level ambition needs to be scaled up: if current pledges were fully achieved this would only cut 2030 emissions about one- third of what is needed, even for the 2oC target.

The case for carbon taxation

Carbon taxes—charges on the carbon content of fossil fuels or their emissions—can play a pivotal role in mitigation strategies, not least because they provides the critical price signal for redirecting investment towards low carbon technologies. A carbon tax of, say, $50 per ton CO2 emissions in 2030 would typically increase prices for coal, electricity, and gasoline by around 100, 25 and 10 percent respectively.

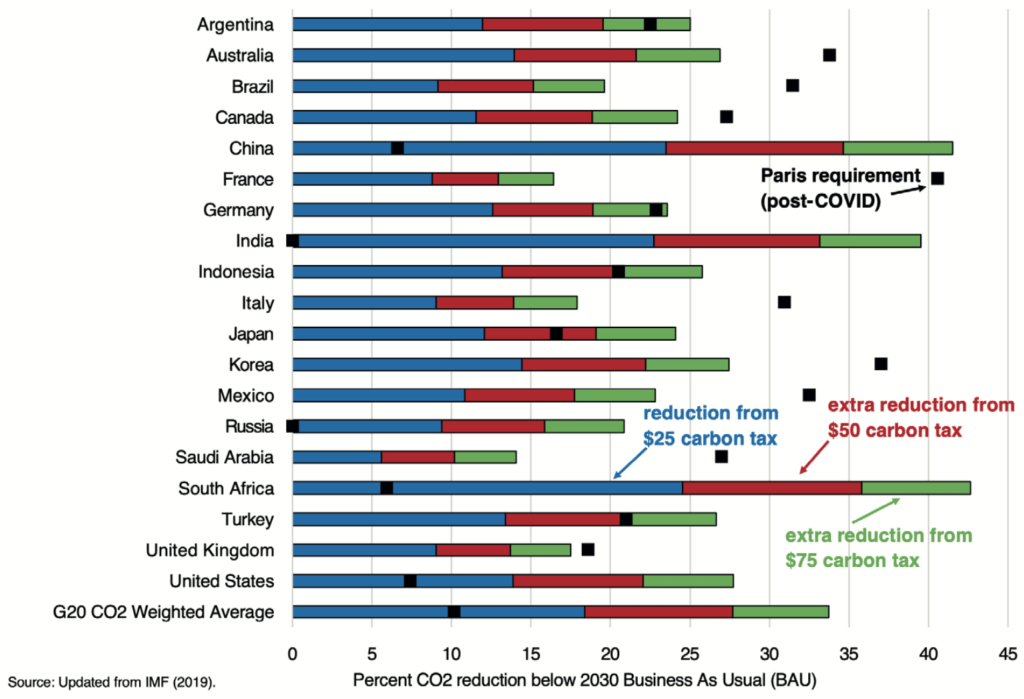

Emissions Reductions for Paris Pledges and from Carbon Pricing

The carbon taxes consistent with countries’ mitigation pledges vary widely with the stringency of commitments, but also in the responsiveness of emissions to pricing, for example, emissions are more responsive to pricing in countries that consume a lot of coal like China, India, and South Africa. For example, a $25 carbon tax by itself would exceed the level needed to meet mitigation commitments in such countries as China, India, South Africa, and United States but even a $75 per ton price would fall short of what is needed in other cases like Canada, France, Italy, and Korea (see figure).

Carbon taxes could also raise significant amount of revenue, typically around 0.5-2 percent of GDP for a $50 tax in 2030. This revenue should be used equitably, and also productively, for example, to lessen the need for higher taxes on households and businesses, or cuts in public spending, as fiscal consolidation packages are put together once economic recovery is well underway to pay off some of the recent debt incurred in crisis-related measures.

Carbon taxes can also generate significant domestic environmental benefits—for example, reductions in the number of people dying prematurely from exposure to local air pollution caused by fossil fuel combustion. And they can be straightforward to administer. For example, carbon charges can be integrated into existing road fuel excises, which are well established in most countries and among the easiest of taxes to collect, and applied to coal, other petroleum products, and natural gas.

Other mitigation options

An alternative way to price carbon emissions is through emissions trading systems where firms are required to acquire allowances to cover their emissions, the government controls the total supply of allowances, and trading of allowances among firms establishes an emissions price. To date, trading systems have been mostly limited to power generators and large industry, however, which reduces their CO2 benefits by around 20-50 percent compared with more comprehensive pricing. It also limits potential revenues from auctioning allowances (similarly carbon taxes, like other types of taxes, often contain exemptions). And although trading systems provide more certainty over future emissions, they provide less certainty over emissions prices, which might deter clean technology investment. They also require new administration to monitor emissions and trading markets, and significant numbers of participating firms, which may preclude their application to small or capacity-constrained countries.

Although over 60 carbon tax and trading systems are in operation at the national, sub-national, and regional level in various countries, the average price on emissions worldwide is only $2 per ton—a small fraction of what is needed. This underscores the political difficulty of ambitious pricing. Where carbon pricing is politically constrained, policymakers could reinforce it with other approaches that do not impose a new tax burden on energy and therefore avoid large increases in energy prices.

A more traditional approach would be to use regulations to control the energy efficiency of products or the emission rates of power generators. In fact, a comprehensive package of regulations could mimic many of the behavioral responses of carbon pricing, though not all of them—regulations cannot encourage people to drive less, or turn down the air conditioner, for example. Regulations also tend to be inflexible and difficult to coordinate in a cost-effective manner across sectors and firms.

A more promising and novel alternative to regulations is revenue- neutral ‘feebates,’ which provide a sliding scale of fees on products or activities with above-average emissions intensity and a sliding scale of rebates for products or activities with below-average emissions intensity. Feebates are especially valuable for sectors that are difficult to de-carbonize through carbon pricing alone, such as the transport sector. By altering the relative price of vehicles with high and low emission rates, feebates could provide very powerful incentives for consumers to buy electric or other zero-emission vehicles without a new tax burden on the average motorist.

Advancing policy domestically

Previous experiences with carbon and broader energy pricing reform across many countries suggest some strategies for enhancing their acceptability. For example, pricing can be phased in progressively to allow businesses and households time to adjust. And an upfront package of targeted assistance, which need only use a minor fraction of the carbon pricing revenues, can be provided for vulnerable households, firms, workers, and communities through, for example, stronger social safety nets and worker retraining programs.

Carbon pricing also needs to be supported by other measures to make it more effective. Besides complementary mitigation instruments like feebates, public investments in clean energy infrastructure are needed (e.g., grid extensions to link up renewable generation sites, pipelines for carbon capture and storage, charging stations for electric vehicles). Technology-related instruments are also needed to addressing market failures at various stages during the invention, development, and deployment of low carbon technologies. Measures are also needed to lubricate climate finance from financial markets, such as carbon disclosure requirements and innovative instruments like green bonds.

The overall policy package needs to be equitable, whether carbon pricing is part of a broader package of fiscal consolidation measures or the revenues are used for broader tax cuts or public investment. The appropriate timing of carbon pricing will vary with national circumstances, perhaps delayed until recovery is well underway for countries able to finance stimulus packages through debt. And consultations with business interests and labor organizations, as well as an extensive public communications program, may help to overcome opposition to the reform.

Advancing policy internationally

At an international level, the Paris mitigation process could be strengthened and reinforced with a carbon price floor arrangement among large-emitting countries. This arrangement would guarantee a minimum level of effort among participants and provide some reassurance against losses in international competitiveness. Coordination over price floors rather than price levels allows countries to exceed the floor if this is needed to meet their Paris mitigation pledges. And the floor could be designed to accommodate carbon taxes and emissions trading systems as well as packages of feebates and regulations if these achieve the same emissions outcome as would have occurred under the floor price.

There are some monitoring challenges—for example, countries would need to agree on procedures to account for possible exemptions in carbon pricing schemes and changes in pre-existing energy taxes that might offset, or enhance, the effectiveness of carbon pricing. But these analytical challenges should be manageable.

Given their lower per capita income and smaller contribution to historical atmospheric greenhouse gas accumulations, a case can be made for emerging economies to have a lower price floor requirement than advanced economies. For illustration, if advanced and developing G20 countries were subject to fairly modest carbon floor prices of $50 and $25 per ton of CO2 respectively, in 2030, mitigation effort would still be twice as much as reductions implied by meeting current mitigation pledges. To reduce emissions to a level consistent with a 2°C target, however, additional measures—equivalent to a global average carbon price of $75 per ton—would still be needed.

Reasons for optimism?

Just three countries—China, India, and the United States—account for about 80 percent of the low-cost mitigation opportunities across G20 countries, so a pricing arrangement among these three countries alone would be a huge step forward and should catalyze action elsewhere. That may seem wishful thinking right now—for example, the United States is set to withdraw from the Paris Agreement in 2020, coal is entrenched in India because of history, large reserves, and existing infrastructure, and China’s nationwide trading system slated for introduction shortly will likely have limited coverage and ambition.

Nonetheless, there are some grounds for optimism. For example, US Presidential candidate Joe Biden is pushing for carbon neutrality by midcentury and carbon pricing. The EU’s Green Deal, announced in December 2019, greatly scales up mitigation ambition and their proposed border carbon adjustment (applied to countries without adequate carbon pricing) could be a mechanism to catalyze carbon pricing elsewhere. Scaling back fossil fuel consumption is in China and India’s own interests when the benefits from reduced air pollution mortality are considered—even a $25 per ton carbon tax in 2030 would save 200,000 premature deaths a year in China and 120,000 in India. And it is in all countries’ interests to see effective mitigation at the international level to stabilize the global climate system and safeguard the environment for future generations.

Finance Ministers have a key role to play in mitigation strategies. Tax systems need to be re-aligning to fully price fossil fuels for their environmental costs, the revenues from carbon pricing need to be managed, mitigation and adaptation projects need to be prioritized in national budgeting procedures, and broader social assistance and fiscal adjustments are needed to ensure the transition to clean energy systems is fair and acceptable to the public.

This article is an extract taken from the Parliamentary Network publication ‘Just Transitions’. You can download a pdf version of the full document here.